"Creative encounter."

Art and friendship: Roxanne Everett, a retrospective.

JANUARY 18—We met in undergraduate school four decades ago and have remained friends since. As can happen in long friendships, life took us in different directions and we lost touch for many years. I hadn’t seen Roxanne in over a decade when one day, as if the universe would no longer allow such distance, we fairly stumbled into each other in the most unlikely place—a steep and deeply shaded urban staircase in a neighborhood of Seattle’s University District. I was on a work break, she was returning home from the University Book Store, arms loaded with art supplies—though it was many years before she would become the artist she is today.

That chance encounter brought Roxanne—and art—back into my life. As friends sometimes do, she saw more clearly than I what was missing in my life, what was possible. Roxanne remembered, when it seems I had forgotten, my love of art.

Roxanne was among the first to visit me during my long years of illness and isolation—that amounted to a kind of exile—and when she came she brought with her a box of exquisite glass beads. She taught me two simple craft items that day and on departing left me with supplies. I never used them. By then my coordination was too poor to string beads, bend wire, attach clasps.

Still, my friend didn’t give up. She brought some of her paintings with her on subsequent visits, solicited my thoughts and opinions on her evolving work and often encouraged me to pick up a paint brush. But after years of chronic fatigue, painting had become unimaginable to me. Instead, I watched with interest and great pleasure as Roxanne blossomed into an accomplished artist.

Friendship. Art. I could not possibly have known the important role each would play in my eventual recovery. Perhaps for that reason I am inspired to explore and celebrate both in Our Journey. It is with pleasure that I offer the following retrospective written by one friend for another.

A love affair with the land.

Roxanne’s earliest paintings reflect eclectic beginnings. At age forty-five she launched her artistic journey, taking workshops and experimenting with a variety of techniques and media, including oil, watercolor, encaustic, mixed-media collage, and acrylic.

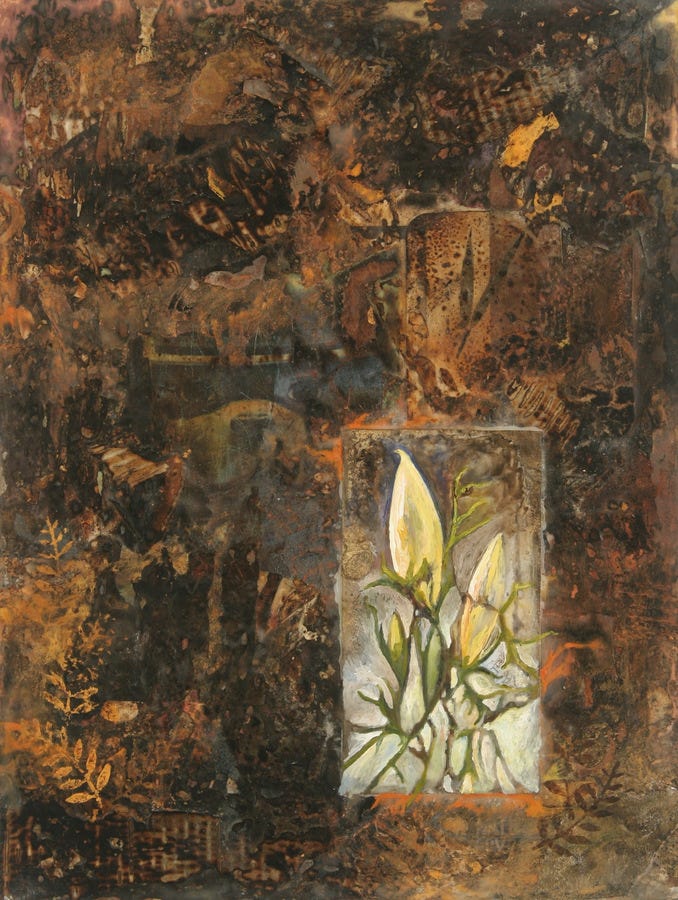

After several years of focusing primarily on collage, she eventually settled on acrylic. Much of her early work is characterized by richly layered surfaces, deeply embossed textures, and luscious colors. An attention to design is informed by her background in architecture.

There are, in her collages, references to western botanical art and Asian aesthetic traditions. These qualities are most apparent in the choice of subjects, juxtaposition of organic and geometric forms, and the absence of perspective in favor of treating the surface as a two-dimensional plane. Flowers, trees, and other flora inhabit densely worked fields of color, where they acquire symbolic significance—less representational than iconic.

Lovely though her early paintings and collages are, for me they never push beyond the decorative. In a recent email exchange, Roxanne had this to say:

My earlier work was experimental, I was learning how to use and mix different mediums. [T]he idea of painting an entire landscape was daunting. Instead, I created interesting textural backgrounds then added something representational—a sketch of a plant for example, to be the main topic. I had never considered them as being decorative but that is probably an accurate thought.

Experimentation, hard work, a willingness to take risks and risk failure: These are the qualities necessary in any art. To a comment I once made recognizing her significant talent, Roxanne demurred: Work and discipline are far more important, she insisted, than any innate ability.

New directions.

An important breakthrough finally came with “Canopy” (see below). For the first time, Roxanne “treated the whole substrate as one painting, rather than a collage or assemblage of several paintings and sketches.”

In “Canopy,” an equilibrium is achieved between space and form. Leaves and branches are in fluid balance within the plane that surrounds them. As in her earlier pieces, the surface is worked in layers, giving it a translucency, but gone are the overtly decorative elements. Here is a bold composition, a new assertiveness. Qualities found in Roxanne’s mature work are already present: attention to composition, flat planes of color rather than subtle gradations, emphasis on negative space, a nascent abstraction.

A second breakthrough piece followed her first (2012) artist residency at Badlands National Park:

My donation piece to Badlands was "Snow Swirl." It was one of my earliest successful landscapes—even more interesting to me now as it is the first to show the smaller shapes and patterns working together to define the entirety.

The Badlands residency was a turning point. By the time “Snow Swirl” was completed in 2013, Roxanne had transitioned to landscapes. Using as inspiration and reference an extensive photo library documenting her time as a ranger with the National Park Service, Roxanne painted many of the remote environments she’d spent so many years working in. It was, she explained, “like writing a love letter to a place I once knew well.”

If 2012 was a year of departure, it also marked a homecoming. With a master’s degree in forest ecology, many seasons spent in the backcountry as a park ranger, and having logged thousands of miles of wilderness backpacking—Roxanne solo-hiked the Appalachian and Pacific Crest trails—the National Park Service Artist Residency Program was a perfect fit.

In landscapes, my friend found her métier—her heart and home.

From Badlands to Iceland.

Artist residency programs gave Roxanne the opportunity to immerse herself in distinct ecosystems and the time, resources, and support needed to translate inspiration onto canvas. She has held thirteen residencies—public and private—in the United States, Iceland, Australia, and, most recently, in Greece. Her paintings are part of permanent collections in five national parks.

With my own familiarity and love of the western lands of the United States, I am most comfortably at home with Roxanne’s paintings of the American West. But it is in her Icelandic landscapes, and those painted subsequently, that her full power as an artist is at last expressed.

Many of the landscapes in this series are constructed out of intricate shapes and patterns fitted together in ways reminiscent of mosaic. As with her early work there remains a palpable Eastern influence: The abstraction, the flat areas of color that define larger forms within the composition, the sparse almost austere palette—all bear a striking similarity to Japanese woodblock prints. This is to my eye, at any rate.

It is, of course, always easy to impose a correlation where none exists. Roxanne denies any conscious reference to Asian art and finds my comparison curious. Still, the creative process is one that taps deeply into the unconscious. We gather images, impressions, and inspiration throughout a lifetime; influences, like deep currents, are often invisible. In the end, art is an experience of the observing mind. Our experience of a painting lies in what we bring to it in any given moment.

Painted from photographs, memory, and imagination Roxanne’s landscapes document unique and uniquely beautiful natural ecosystems, many of them threatened. While deeply personal expressions of one woman’s love of the land, they transcend time, place, and the personal to acquire that iconographic significance I mentioned earlier.

Whether or not we are aware of it, our identities—our very beings—are intimately connected with the land upon which we live. For that reason, these paintings point to subtle issues and dynamics of alienation and belonging. They raise questions about relationship and stewardship. Evoking our primordial and familial connection with the land—with Earth, our common home—Roxanne’s work touches the sacred.

A gift of art and friendship.

When I first saw “Late Afternoon in the Fossil Beds,” it was as if I stood on a vast prairie with an endless sky overhead, the earth firmly beneath my feet, wind blowing the grasses around my legs, sun warming my face. In the landscape of my imagination, brought vividly to life by Roxanne’s painting, there was no illness, no infirmity, no suffering—I was free.

When I could no longer hike the mountains and forests, Roxanne’s landscapes offered connection to a larger world—to the natural world I so loved and missed. Gazing at “Forest Spring,” I felt myself on the soft leaf-strewn ground of a woodland trail. As my personal world narrowed, becoming ever more claustrophobic, my friend’s paintings were a source of beauty and joy—a reservoir of hope and possibility.

One day in 2016—after years of encouraging me to do so—I sent Roxanne an email asking about materials I would need to begin painting. A week later, to my surprise and delight, a package from Roxanne arrived on the doorstep—it was full of acrylic paints. I picked up a brush and began my own creative journey.

This is my letter of love and gratitude for Roxanne.

Note: You can find an extensive portfolio of Roxanne’s paintings on her website here.

Can I love this times 1,000? Thank you Cara! ❤️